All Politics are Reproductive Politics

- Giulia Cavalcanti

- Oct 21, 2020

- 4 min read

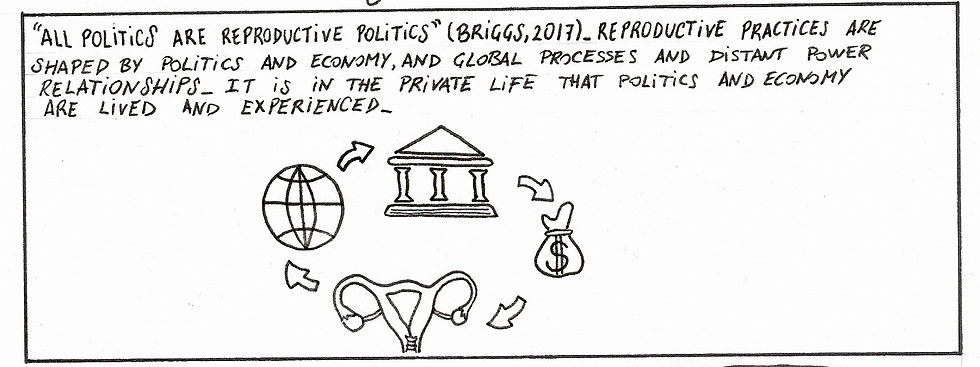

Laura Briggs (2017:18) states: “all politics are reproductive politics”.

This means that politics and economy, and global processes and distant power relationships in general shape local practices around reproduction, such as having and raising children, provision of safety, physical and emotional care towards dependant people, and insurance of their and one’s own survival (Briggs,2017:2,105–6; Ginsburg and Rapp,1991:313–6).

“All politics are reproductive politics” means that the lives and experiences of individuals can only be understood by contextualising them in light of politics and economy, as it is in the household that politics and economy are lived and experienced (Briggs,2017:4,18).

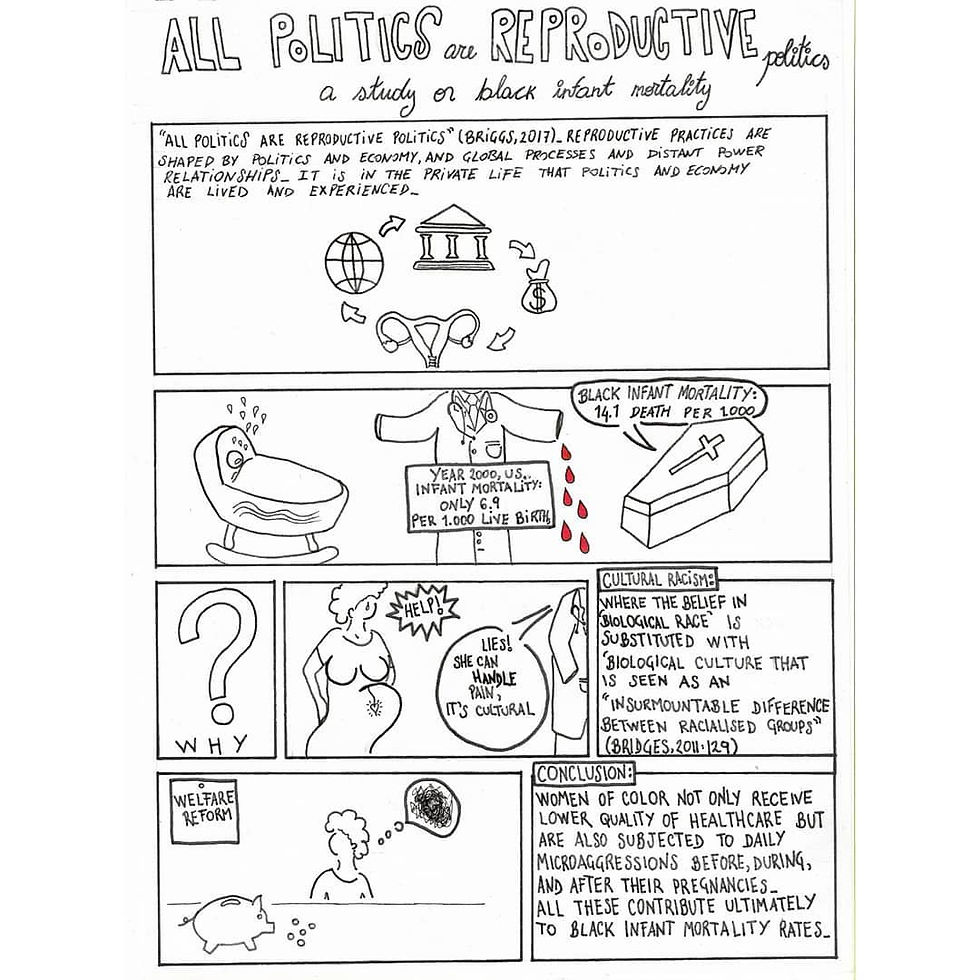

To better understand Briggs’ statement infant mortality will be introduced.

In 2000 the national US average of infant mortality was 6.9 deaths per 1,000 live births. However, infant mortality among African Americans had a rate of 14.1 deaths per 1,000 live births. Black infant mortality was and still is two and a half times higher than white infant mortality (Bridges,2011:108).

These statistics have been justified by mainstream literature and media as a result of the socio-economic conditions of people of colour, that is, in terms of class, and as a consequence of individual attitudes and choices, such as unhealthy eating habits and smoking habits (Bridges,2011:108–12,120–3; Briggs,2017:128–9,135–7).

These justifications, however, are not able to fully explain the issue of infant mortality. These justifications, in fact, employ an individualistic approach that does not contextualise infant mortality within politics and economy (Briggs,2017). Further, these justifications do not hold up in the face of the findings of the 1992 study carried out by Schoendorf and Hogue that found the same racial disparities around infant mortality when comparing white and black pregnant women whose behaviours and socio-economic conditions were the same (Briggs,2017:138–9).

“All politics are reproductive politics” in the context of infant mortality means placing infant mortality in relation to a global, cultural phenomenon, that is, cultural racism and more broadly racism in general (Bridges,2011:108–12).

Cultural racism is a modern form of racism, where the belief in a biological race — the belief in biological differences between different racialised groups of people — has been substituted now by the belief in biological culture (Bridges,2011:131–8). Both racism and cultural racism share the perception of the existence of an “insurmountable difference between racialised persons and groups” (Bridges,2011:136). Simply put, cultural racism consists of employing the word ‘culture’ as a euphemism for ‘race’ (Bridges,2011:132).

What does this have to do with the healthcare provided by physicians, you may ask?

Well… A physician’s personal beliefs can have an effect on the way one practices medicine. In fact, throughout history, within the healthcare system, personal beliefs and especially cultural racism and racial stereotypes have been the justification for racist medical practices.

For example, based on the racial stereotype of Black and Latino women as sexually loose, “gynaecologists would almost automatically diagnose a black woman with symptoms of endometriosis as having pelvic inflammatory disease (Hoberman,2005:95 cited in Bridges,2011:129).

De facto, the Institute of Medicine (2005) found out that what differentiated black pregnant women from white pregnant women was not the socio-economic living conditions, but the “lower quality of healthcare” received (Bridges,2011:111).

However, as previously said, local practices around reproduction to be fully understood must be placed and contextualised not only in terms of global cultural processes but also in terms of the changes of politics and economy (Briggs,2017:4,2,18,105–6; Ginsburg and Rapp,1991:313–6). Thus, black infant mortality must be placed and contextualised within the changes of politics and economy that have occurred in the US, specifically after the 1980s, when racial disparities around infant mortality have increased (Briggs,2017:128–9).

With neoliberalism and the introduction of the welfare reform after 1980, the figure of the welfare queen has arisen. That is, the person who is uneducated, but smart enough to live upon the maintenance from the government (Bridges,2011:212–3,226–9; Briggs,2017:11–2). The welfare queen, however, was constructed in the common imaginary as black, because according to the Conservatives — behind the campaign of the welfare reform — black communities were the ones who needed most welfare, but at the same time did not deserve it, because their necessity of welfare was a simple result of their being “lazy” to work (Briggs,2017:12,131).

Women of color not only receive a lower quality of healthcare, as previously argued, but are subjected to daily microaggressions — due partly for being of colour, and partly for being identified as welfare queens — before, during, and after their pregnancies. These microaggressions, together with the receipt of lower quality of healthcare, contribute ultimately to black infant mortality rates (Briggs,2017:129,131,147; Bridges, 2011).

Concluding, black infant mortality and the healthcare system, in general, are reproductive politics because the changes that occurred in the politics and economy arena (i.e. the welfare reform), together with the global cultural process of cultural racism have affected the personal lives of black women and their lost infants. These, furthermore, have influenced how the white hegemonic population, including physicians, perceives and treat people of colour. In turn, the provision of lower quality of healthcare by physicians have created ultimately a structural system that works concurrently and, therefore, is equally responsible for the death of black infants.

Bibliography Bridges, K. (2011) The “Primitive Pelvis,” Racial Folklore, and Atavism in Contemporary Forms of Medical Disenfranchisement. In: Reproducing Race: An Ethnography of Pregnancy as a Site of Racialization. London: University of California Press, pp. 104–43 Bridges, K. (2011) Wily Patients, Welfare Queens, and the Reiteration of Race. In: Reproducing Race: An Ethnography of Pregnancy as a Site of Racialization. London: University of California Press, pp. 202–50 Briggs, L. (2017) Introduction. In: How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics: From Welfare Reform to Foreclosure to Trump. Oakland, California: University of California Press, pp. 1–18 Briggs, L. (2017) The Politics and Economy of Reproductive Technology and Black Infant Mortality. In: How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics: From Welfare Reform to Foreclosure to Trump. Oakland, California: University of California Press, pp. 101–48 Ginsburg, F. and Rapp, R. (1991) ‘The Politics of Reproduction’. Annual Review of Anthropology, 20(1), pp. 311–43

Comments