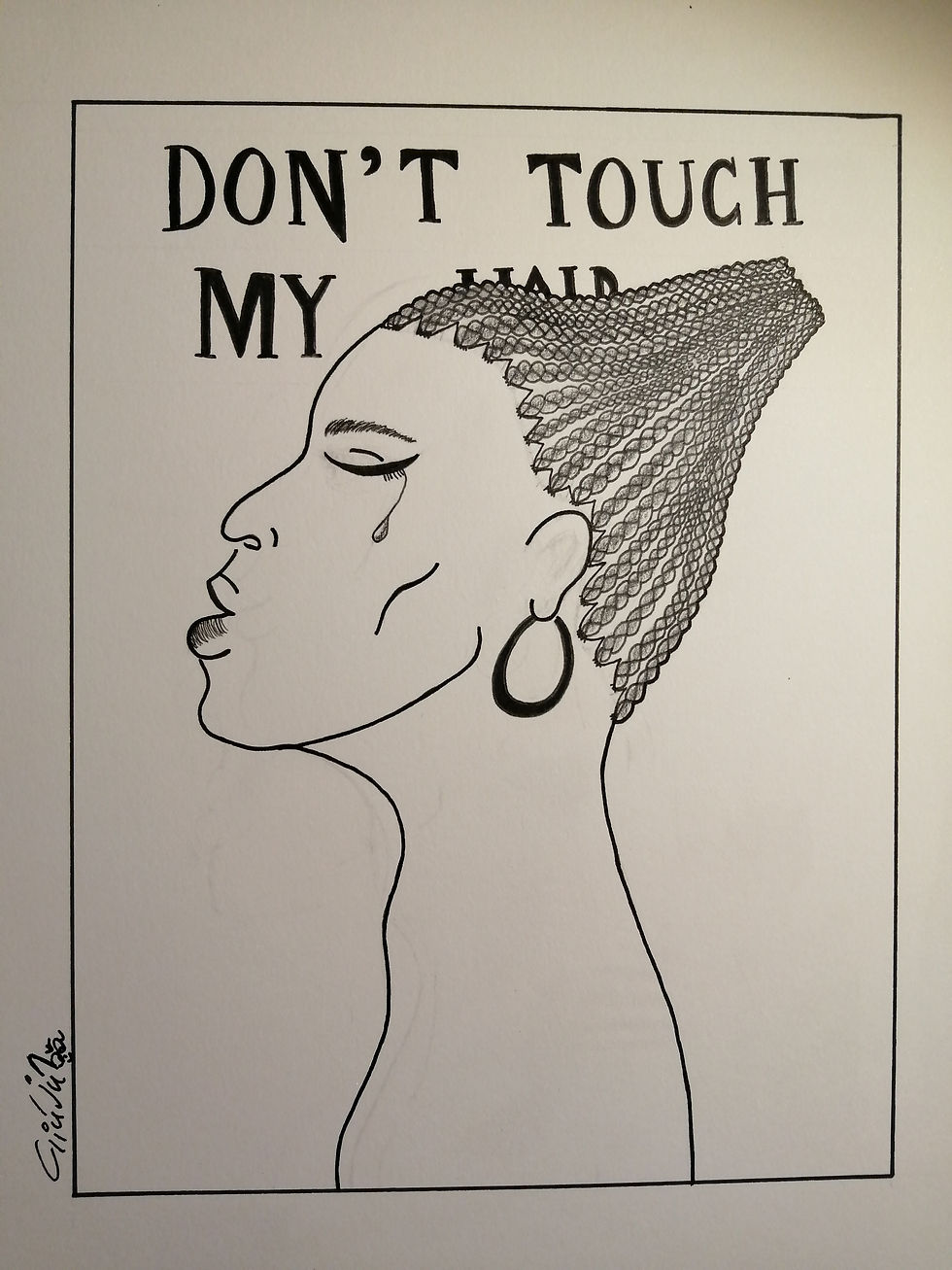

When hair becomes Resistance

- Giulia Cavalcanti

- Feb 16, 2021

- 4 min read

‘Don’t touch my hair’ by Emma Dabiri revolutionised my white idea of race. Every page turned is a new surprise, a piece of new knowledge gained. Every page turned is a new ‘WOW’. Literally.

Who would know that black and white aren’t just about colour, but also and mainly about hair?

Who would know that racism isn’t just about colour, but also about hair?

Who would know that hair can be a political symbol, a political act?

Who would know that time is money, and that time is hair?

Who would know that hair was the base for punishment back in the dark times none dares to name? S L A V E R Y.

Who would know that Afro hair is “not necessarily aesthetically African”?

Who would know that “the possession of beauty could compensate for […] racial inadequacy”?

Who would know that the queens of pop are all about black culture?

Who would know that hair is about “the mathematical and philosophical concept of infinity”?

Well… Emma Dabiri knows all of that. And if you dare to read ‘Don’t touch my hair’ you would know it too…

Through a biographical essay, Emma Dabiri takes us through her childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Through a biographical essay, Emma Dabiri gives us a taste of her pain, tears… Pain and tears of “…all the black brilliance and beauty, squandered and diminished yet never extinguished”.

Is to these men and women that Emma Dabiri dedicates her book.

‘Don’t touch my hair’ feeds us with pain, tears, and scientific knowledge. Because, after all, racism was born out of science. Fake science. Racist science.

From chapter one, Emma Dabiri drops us a (symbolic) bomb.

Blackness isn’t just about colour, but also and mainly about hair.

Racism isn’t just about skin colour, but also about hair.

Sarcastically enough the chapter is called ‘It’s only hair’.

And hair isn’t just hair. “Braiding operates as a bridge spanning the distance between the past, present and future. It creates a tangible, material thread connecting people often separated by thousands of miles and hundreds of years”.

After an introduction of the physiognomy of hair, from 1 to 2a, 2b, 2c, 3a, 3c, 4a, 4b, and 4c – from straight to kinky hair – it’s kind of obvious the meaning of the title of the second chapter: ‘ain’t got the time’.

Capitalism, working 9 to 5, and time as we know it are not natural, are constructs that do not suit human beings especially the ones with kinky hair.

“…black people have been robbed of the time they once enjoyed in abundance”.

“…in traditional African time, time has to be created or produced. […] ‘Man is not a slave of time; instead he “makes” as much time as he wants’”.

“Can you imagine running a brush through your hair and done?”

Black people [read: people with kinky hair] ‘ain’t got the time’.

Capitalism, working 9 to 5, and time are constructs that guess riddle… come from Colonialism. The time when Eurocentrism started. Yes, this is when everything – and I mean everything – was compared to the white European standards. Including hair!

The solution? Reclaim your time, reclaim your hair (and Emma Dabiri doesn’t mean European white hair)!

Yet, despite the well-known Colonial history, black hair was told to just shut up and relax. Literally. And this is where Emma Dabiri welcomes us in chapter three: ‘Shhhh… just relax’.

And this is the story – nothing like a fairy tale – of how kinky hair became straight hair, of how black women became infertile and died of cancer.

And to think that Afro hair can achieve infinite “ranges of styles and textures […] from relaxer, to weave, to intricate braiding patterns”.

And after having achieved the boring(!) white hairstyles, alongside infertility and cancer caused by the chemicals used in straighteners, blacks were even accused of being pretentious for adhering to White fashion standards!

Who’s responsible? Colonialism, of course.

After all, “…the most destructive consequence of colonialism was […] the control of the minds of the people”.

But the famous Annie Malone and Madam C.J. Walker with their strategies “…of associating heavily processed straight hair with looking natural” are at fault too.

In a world where black presence is glorified and celebrated – like Netflix did with Madam C.J. Walker –, Emma Dabiri reminds us that representation isn’t synonymous of liberation. Representation must be questioned. In chapter four, ‘how can he love himself and hate your hair?’, Emma Dabiri fearlessly question these representations alongside “the implicitly white and implicitly patriarchal” origins of the ‘Black is Beautiful’ movement.

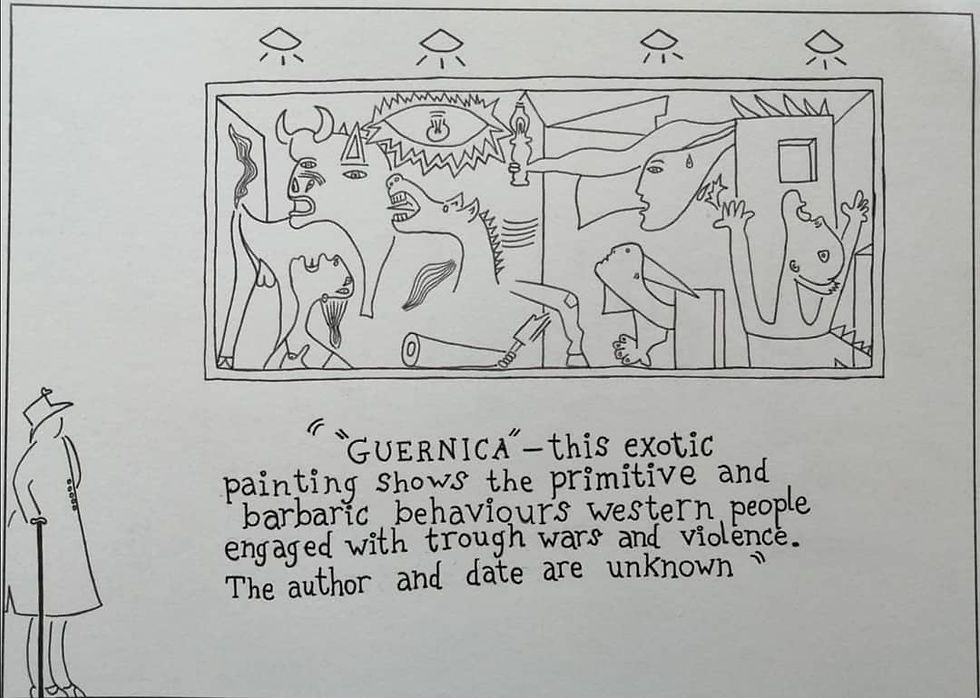

In chapter five, ‘everybody wants to sing my blues, nobody wants to live my blues’, Emma Dabiri fearlessly and endlessly continues to remind us to always question. From the 1990 hit ‘Vogue’ by Madonna to Elvis Presley. The systemic extraction of African and Afro-diasporic resources – physical, cultural, and material –, started with Colonisation, continues until this day.

This systemic extraction now called cultural appropriation often puts the attention to black peoples’ excellence in the performing arts. However, the infinite “ranges of styles and textures […] from relaxer, to weave, to intricate braiding patterns” – as presented in the final chapter ‘ancient futures: maths, mapping, braiding, encoding’ – are testimony of blacks’ excellence in maths, geometry, and philosophical concepts of infinity. But most importantly, a testimony of blacks’ expertise, creativity, and resistance through their hair over millennia.

In conclusion, Emma Dabiri’s ‘Don’t touch my hair’ surmounts the significant challenges posed by the lack of historical record “when our interest is in black lives. Black life has not been archived or documented in the same way that white life has. There are no oil paintings that display our wealth and power. We are present, but you have to look for us elsewhere, perhaps in the language you use, in the way you dance, in the food you eat, in the computers you use […], in the art you make or the music that is the soundtrack to your life…”.

I hope that my words do justice for such an inspiring book. I would like to thank the author, Emma Dabiri for this. I would also like to thank @itsajart for teaching me (without knowing) how to draw cornrows!

Comments