Museums, holders of… Institutional Racism

- Giulia Cavalcanti

- Oct 21, 2020

- 6 min read

Museums are believed to be the beholders of knowledge.

Museums tell the histories and stories of mankind.

But, which stories and histories are being told, and from which point of view?

Let’s take First Nations peoples…

Museums have had fun telling the histories of First Nation peoples throughout time, by presenting them as primitive, exotic and authentic.

Museums have made First Nation peoples interesting and appealing to the eyes of a white audience exactly because of their apparent exoticism and primitivism, and authenticity, that is, their believed inherent ability to be a testament of the history of human development, especially around the existence of an authentic time before the arrival of the Western man (Clifford, 1988: 227–8; Whitelaw, 2006: 202–3).

Museums have told First Nations’ and white audiences that First Nations peoples are primitive, exotic, authentic. Museums have told the story that First Nations peoples are no longer alive on this planet (Whitelaw, 2006: 203).

Consequently, First Nations peoples have been tainted by their “ethnological fate of always being presented and treated as anthropological specimens” (Ames, 1992: 79).

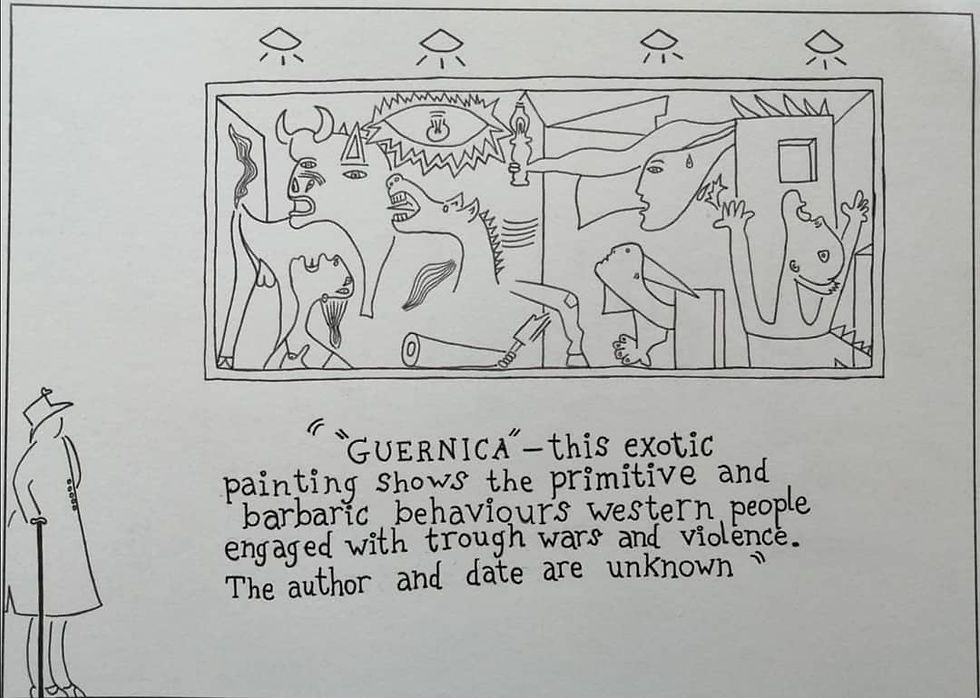

What if museums would present the ‘Guernica’ by the famous painter Pablo Picasso in the same way that First Nations peoples and their cultural material objects are always presented?

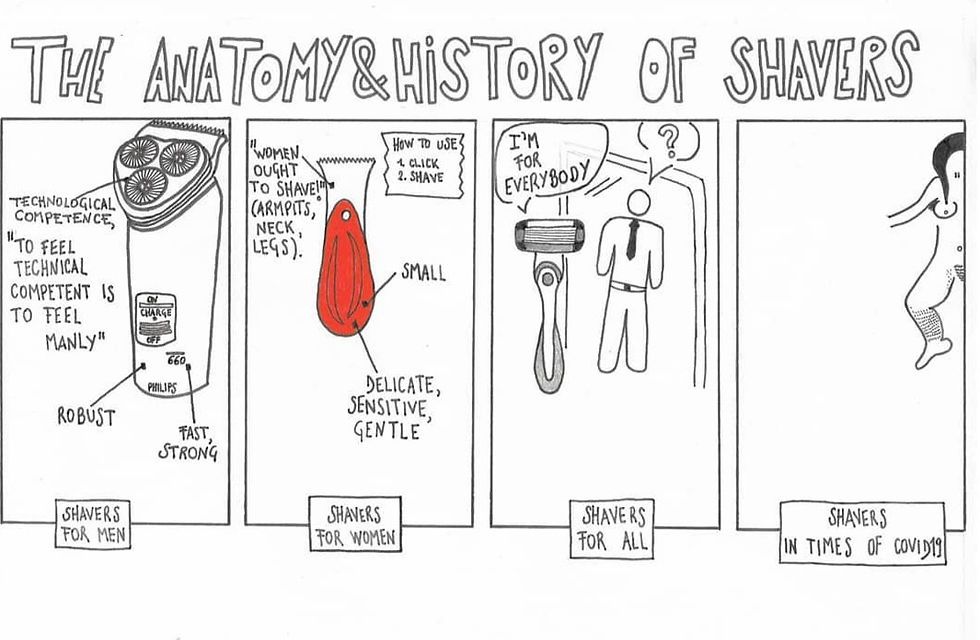

Primitivism, authenticity and exoticization are not inherent characteristics of First Nations peoples and their cultural material objects. They are produced by the strategic curatorial practices that emphasise, confirm and contribute to the existing order of meaning and social beliefs(Acord, 2010: 461; Ferguson, 2005: 128–30). These strategic curatorial practices include displaying First Nations peoples’ cultural material objects as anonymous and/or in isolation, using high-contrast lighting, and using the past tense when referring to them. These curatorial practices create a sense of mystery that ultimately gives the objects displayed a sense of being primitive and historical, that is, belonging to the past and having no continuity with a living society (Whitelaw, 2006: 203; Frank, 2000: 164–5, 171; Clifford, 1998: 226–7).

So, how First Nations peoples’ cultural material objects would be presented if the same curatorial practices employed to present Western artists and their cultural material objects would be employed to present First Nation peoples?

Sowhat existing order of meaning and social belief do primitivism, authenticity and exoticization refer to?

It must be clarified that the concepts of primitivism, exoticization, and authenticity do not exist in a vacuum, but rather are a projection of the wider society mentality. Specifically, these concepts are a projection of what Clifford (1987) calls the salvage paradigm, that is the 20th-century anthropological belief according to which the preservation of artifacts coming from pre-contact ‘primitive’ societies was necessary as a testament of the existence of an authentic period of time free from Western traces.

This, in turn, was a reflection of the believed and foreseeable disappearance of the cultures’ primitive and authentic character due to their inevitable assimilation with Western culture. This great zest towards the preservation of cultural material objects, however, did not concern the preservation of those individuals who had produced these same objects.

This aspect, within the museum setting, is evident in the museums’ inability to establish a connection with First Nations peoples living today (Whitelaw, 2006: 202–3; Clifford, 1988: 231). This shows how — as initially argued — First Nations peoples’ cultural objects were valued for their believed inherent ability to tell history (Clifford, 1988: 227–8), specifically of “a vanishing culture, and … imagined pre-contact authenticity that could not be recovered” (Whitelaw, 2006: 204), and thus their solely ethnographic significance, rather than aesthetic (Whitelaw, 2006: 205–6).

So, how curatorial practices would look like if museums would tell the “”truth“”, if museums would tell the histories and stories of First Nations peoples from their own perspectives? So, how curatorial practices would look like if museums would tell their intent and interests without filters?

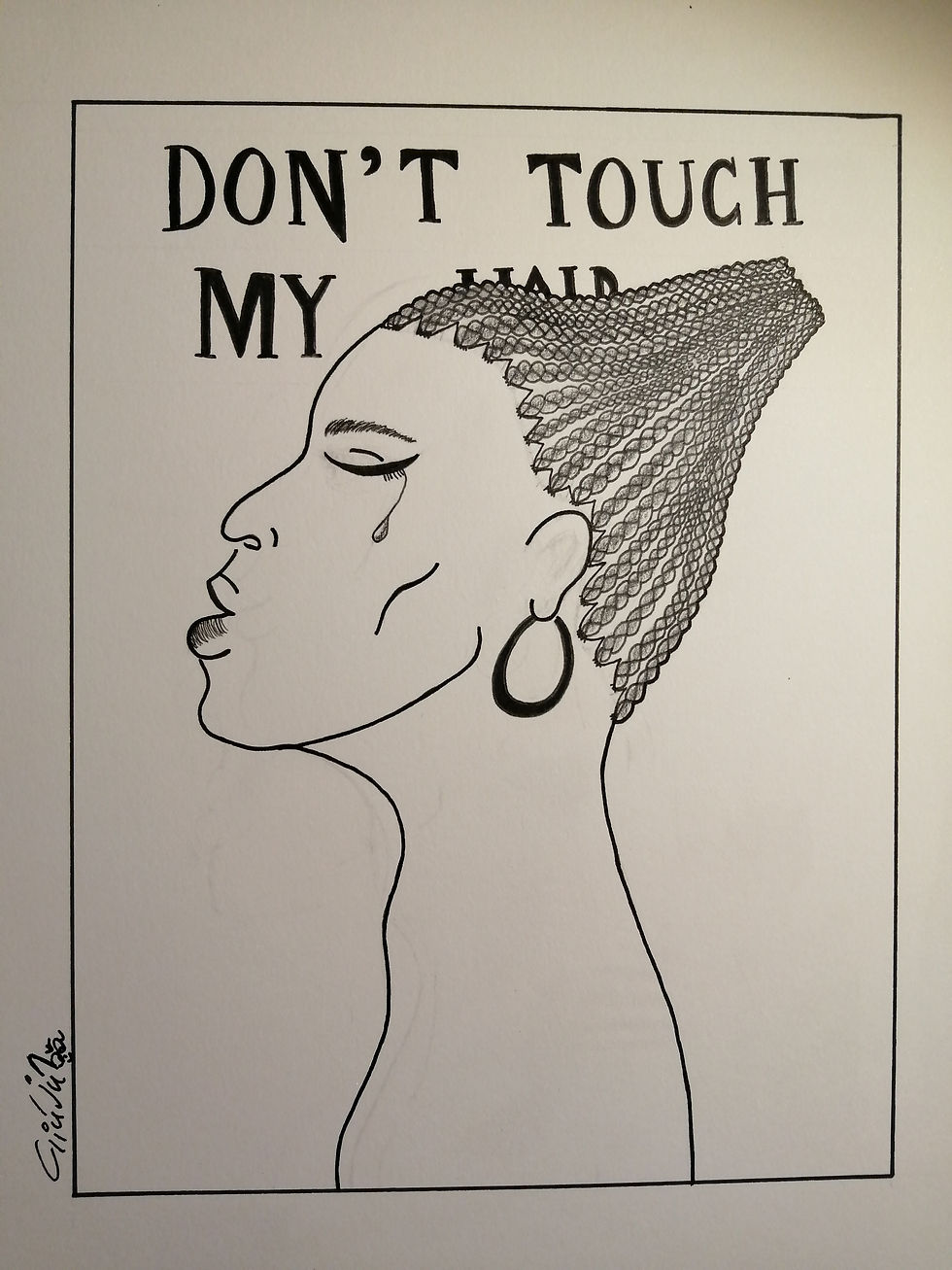

The salvage paradigm belief that is projected into the concepts of primitivism, authenticity and exoticisation, that are, in turn, projected into the ways of curating and doing museums produces symbolic violence against the First Nations peoples who live today.

Symbolic violence consists of the imposition of a cultural paradigm, that is, systems of symbols and meanings upon society. This is made possible through the imposition of the dominant culture and its interests, that become internalised in the minds of the whole society. All this is made possible thanks to the imposition and employment of non-coercive cultural mechanisms — such as representation within museums — that, in turn, is made possible thanks to the presence of a pedagogic authority, that is, that individual or institution — such as museums — who is given the arbitrary and power to act, or better to impose these systems of symbols and meanings. The figure of a pedagogic authority (read: museums) is key for the imposition of those symbols and meanings belonging to the dominant culture because such a figure is the one that gives the external illusion that this process is legitimate. Finally, symbolic violence and all the elements and processes that constitute it produce ultimately the reproduction of the power relations and social structure of which the dominant culture is made of (Jenkins, 2002: 103–7). Finally, the repetitive way of representing First Nations peoples according to the dominant culture’s perspective — that is, as being oppressed, victims, primitive, exotic and belonging to a past that is limited to colonial history and that is no longer recoverable — produces the reproduction of power relations and the social structure of which it is made of. Through these curatorial practices and repetitive way of representing First Nations peoples, First Nations peoples today are inculcated with such beliefs and are made to believe that the portrait provided by western museums and its exhibitions around themselves are their own true identities (Jenkins, 2002: 103–7; Clifford, 1988: 227–8; Whitelaw, 2006: 204). For example, Frank (2000: 168), who is a native herself, recalled how she felt at unease about her own identity and doubted being ‘truly’ Indian in front of the way the Royal British Columbia Museum had portrayed and represented Canada’s First Nations peoples.

What are the interests of museums, then? The ways in which museums and exhibitions portray and represent First Nations peoples, it could be argued, are part of a larger project, namely, social identity formation. On the one hand, symbolic violence creates in First Nations peoples a social identity that is primitive, exotic, authentic, that in other words — it could be argued — has the appearance of their own ancestors at the times of colonialism. On the other hand, Western peoples are made to believe that First Nations peoples’ social identity corresponds to the one represented within museums and that their own social identity is opposite to and independent from the one being portrayed (Wolfe, 2006: 387–90; Hutcheon, 1995: 10–1, 15). The settler society shapes its own social identity by pursuing “…to recuperate indigeneity in order to express its difference — and, accordingly, its independence — from the mother country” (Wolfe, 2006: 389). In other words, the repressed Native allows the formation of the settler society as free and powerful (Wolfe, 2006: 387–90; Clifford, 1988: 220). Indeed, it must be emphasised, the imposition of systems of symbols and meanings (i.e. primitivism, authenticity, exoticisation) is also imposed upon western visitors (Jenkins, 2002: 104).

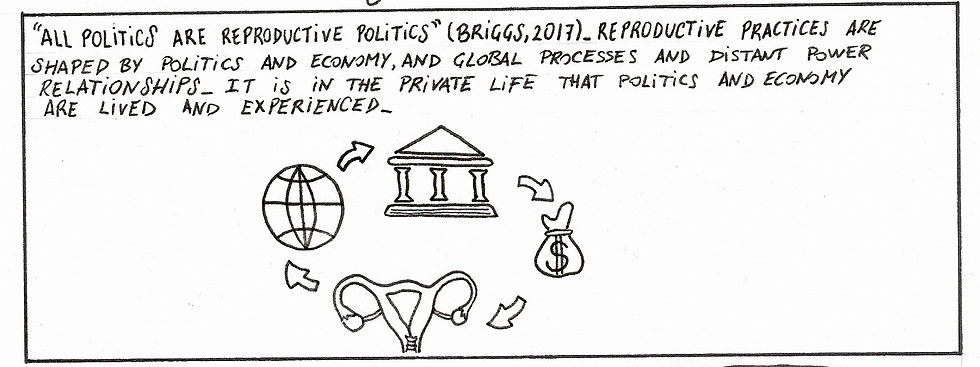

This double-edged social identity formation, it could be argued, lies behind the interests of the dominant culture, that is, maintaining the social structure and power relations, where the Western world occupies the place of the powerful and the First Nations peoples the place of the powerless (Jenkins, 2002: 104–5; Wolfe, 206: 387–90).

Having considered the symbolic violence produced upon First Nations peoples living today — brought by those curatorial practices that represent First Nations peoples as primitive, exotic, and belonging to the past — it becomes clear that those same curatorial practices must be defeated. This is even more urgent considering the role of museums as upholders of knowledge previously outlined.

This article would not be complete if I would not present you how those racist curatorial practices are being defeated.

(Pointing out institutional racism is a must. However, to be an anti-racist — I believe — also consists of pointing out the changes and acts of resistance that are brought within the museum practice).

The defeat of the An example of the defeat of the curatorial practices that have caused symbolic violence against First Nations peoples today is being carried out by First Nations artists themselves, or better artist-warriors. These artists have appropriated themselves of western ideas, thoughts and language, but their use of art consists of a “site of political and cultural change” (Houle, 1991: 35 cited in Kramer, 2004: 173–4). Artist-warriors — such as John Powell’s Sanctuary, part of the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, Canada — create art that challenges and disrupts the western idea of what constitutes ‘authentic Indian art’ as being traditional, spiritual, mythic, mysterious, and rural. In other words, artist-warriors demonstrate how Nativeness can be conceived in less extreme ways (Kramer, 2004: 173–4; Clifford, 2001: 483).

Comments