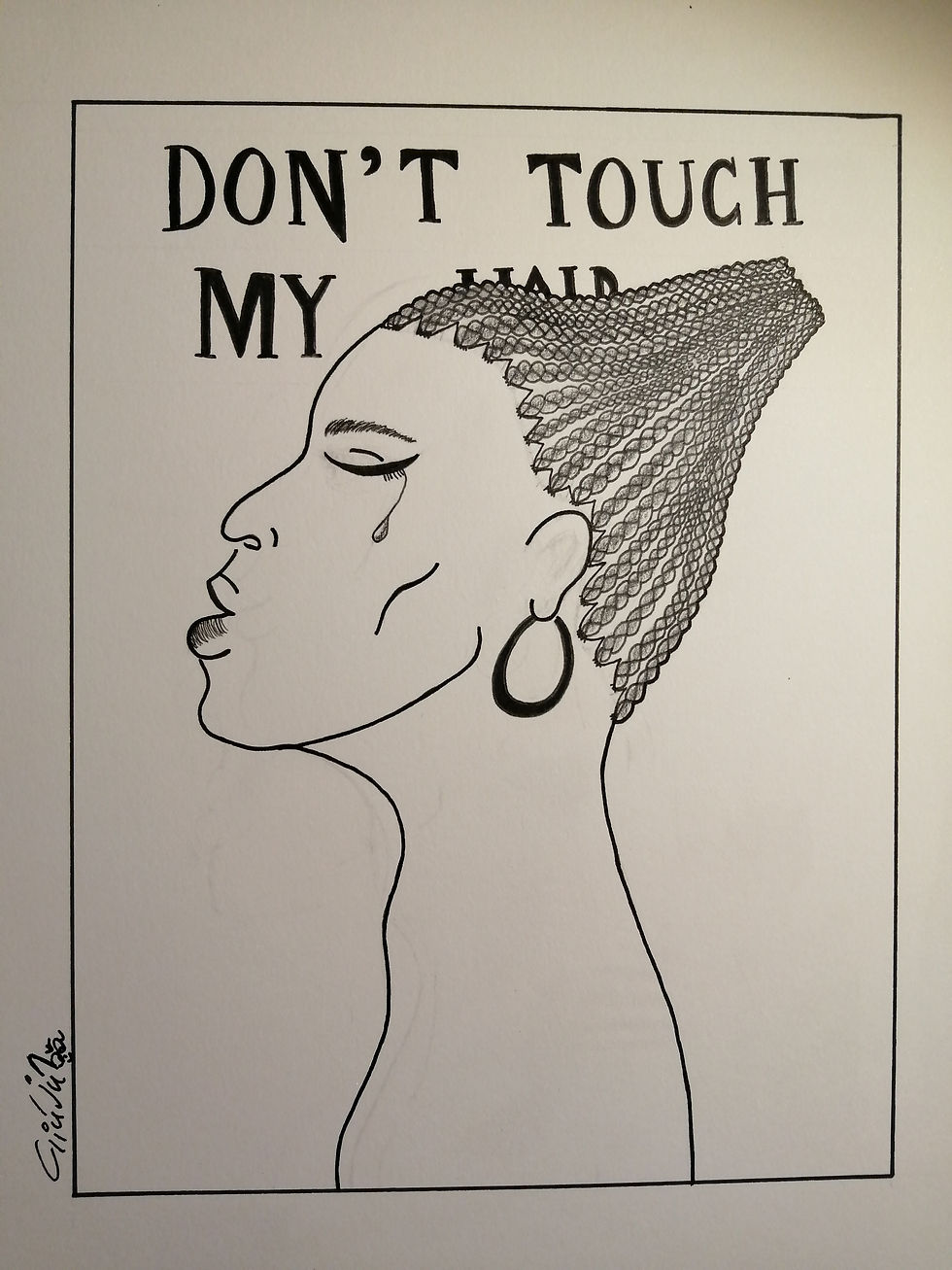

Travestis, and their right to exist

- Giulia Cavalcanti

- Oct 21, 2020

- 4 min read

How do we know ourselves? Female, male, non-binary, third-gender, and travestis… The options are infinite! But how do you know your gender? Well… Anthropology can help you with that. To be more specific, Audre Lorde’s erotic and Davis-Floyd’s authoritative knowledge can help you with that

The erotic and authoritative knowledge are two systems of knowledge that inform individuals’ actions, but with different social processes (Lorde, 2017:27; Jordan, 1997:58). While authoritative knowledge informs individuals’ actions, because its efficient and structural superiority character legitimises them (Jordan, 1997:56); the erotic, on the other hand, informs individuals’ actions, because the bodily and internal feelings guide individuals towards them, or, put more simply, because it feels right to them Today, Judith Butler (1993) theorisation of gender as being fluid and a socially constructed concept is widely accepted.

However, the knowledge of ourselves rooted in each of us’ erotic is highly dependent upon the authoritative knowledge, that is, the dominant way of knowing ourselves, the knowledge that counts, namely the binary female-male.

Gender, however, is not limited to the binary female-male.

Let’s have a look at travestis in Brazil, studied by Don Kulick (1997).

Travestis are those individuals who were born biologically male, but who perform the female gender. This is primarily done by wearing typically feminine clothes (e.g. dresses and high hills). In fact, the term ‘trasvestir’ in Brazilian Portuguese means “to cross-dress” (Kulick, 1997:575).

The female gender is also performed by embodying women’s bodies, that is, modifying their bodies according to the Brazilian beauty standards.

Most importantly, for travestis to be feminine and to be like a woman means to perform sexuality as women do. Specifically, it means to be penetrated.

However, despite their highly feminine features, travestis do not want to and do not go through sex reassignment surgery. Indeed, travestis highly value their genitals, and above all, they do not feel trapped in the wrong body and do not identify themselves as women in terms of essence. Rather, “…they feel themselves to be “feminine” …or “like a woman” …in terms of behaviors, appearances, and relationships to men” (Kulick, 1997:577).

“For three years he was a man for me, and after those three years he became a woman. I was the man, and he was the woman […] he penetrated me… and I sucked [his penis]. […] It changed with… he gave me his ass, started to suck [my penis], and well, there you are” — Tina (Kulick, 1997:580). Therefore, gender within the Travestis’ community is defined by what one does with one’s genitalia, rather than by what genitalia one possesses. The binary that counts is the binary between men and non-men.

Travestis’ understanding of themselves is achieved through the erotic, which also corresponds to the authoritative knowledge.

This understanding of oneself within the Travestis community — based on the binary male/non-male — is the only possible and obvious way of understanding gender.

Despite this, “Brazilian travestis have historically been pathologized, criminalised, ridiculed and killed” (Diehl, et. al., 2017:391).

This is enhanced by the Brazilian institutions that do not allow travestis’ change of name, and by those strands of academia that frame travestis under the terms ‘third gender’, ‘transgender’ and ‘transexual’ that base their judgment on the authoritative knowledge and cultural authority that sees being either female or male as the only possible way of existing (Diehl, et. al., 2017).

As a result, travestis are neglected the right of existing according to what they feel they are, that is, their erotic. In other words, travestis are denied their human rights according to the Declaration of Human Rights that states that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2012 cited in Diehl, et. al., 2017:396).

Finally, allowing travestis to exist according to what they feel they are would lead to a step towards a holistic questioning of the binary female-male and, most importantly, towards decolonisation. This would break ultimately the pattern, also inherited by colonisation, according to which the global north establishes and dictates the acceptable understanding of the world, that is, what the norm is (Silva and Ornat, 2016:21–5; Campbell, 2011:1456–8,1466–7; Grech, 2015:13–5; Williams, 1987:135–6).

Allowing travestis to exist according to what they feel could end ultimately the symbolic oppression from the global north upon the global south.

Comments